December 1, 2002

Column 132

A Labor of Love

It had to be a joke.

When I flipped on my laptop the other day and polled for messages, buried among the list was a curious return address: [email protected]. Could it be? I immediately clicked away.

The e-mail was from John Lowe. One of the greatest darters to ever step to the oche, winner of more than a thousand tournaments, had sent ME a message.

I scrolled down. I was amazed.

It turns out that “Old Stoneface” counts himself among the half-dozen, mostly sexist men who smoke banana leaves, who read the drivel I knock out each month in my column, “Dartoid’s World.” Clearly, Lowe’s moniker should be changed to Old Stonedface.

His message was brief. He wanted to know if I could get him a hooker.

No. No. THAT message was from John Part.

The gist of Lowe’s message was that he was working on a couple of new projects, his fourth book and a special web site. Doctor of Darts, Patrick Chaplin, was doing a piece. Lowe wanted to know if I would contribute a chapter.

So I popped off a return e-mail. “Me? You want something from me? Who is this really? Steve Brown?”

A few days later another message appeared. “I’m not looking for a piece from somebody who’s ‘been there, done that.’ I’m looking for something from someone who’s ‘been there, seen that.’ You’re probably the most traveled darts person outside of the professional ranks. Barry Twomlow had that distinction until his retirement. I would ask you to write as little or as much as you possibly can.”

He wrote that he was looking for some “funny stories” and he had some of his own. For example, one time Lowe threw at the “top of the CN Tower in Toronto whilst some cowboy was yodeling.” Another time he “played on a cruise liner whilst sailing through the Bay of Biscay in a nine-force storm.”

So I wrote him back again. “What’s a ‘whilst?'” I asked.

Actually I explained that, while honored to be asked to contribute to his projects, I felt out of my league. “I’ve also been in the CN Tower,” I wrote, “but I got thrown out for playing strip-pool in the lobby. While it’s true that I traveled a lot, except for being pretty certain I hold the record for the most consecutive 26’s ever thrown and once being defeated by my dog. I really don’t have any claims to fame. I’ll do what I can.”

So I dug into my files.

Over the years I’ve enjoyed some amazing experiences. I’ve bicycled 2,000 miles from Dublin to Moscow. I’ve polled a dug-out canoe down Botswana’s hippo-infested Bora River. I’ve white-water rafted Zimbabwe’s Zambezi River. I’ve tracked mountain gorillas deep into Uganda’s Impenetrable Forest. I’ve ventured 500 miles up the Congo River in search of elephant poachers. Basically, I’m just a big, damn dummy.

Along the way I have been earnest in my search for the Holy Grail — the perfect game in the perfect darts-dive. And, of course, the perfect beer.

On six of the seven continents and in more than sixty countries I have had the pleasure of going toe-to-toe and mug-tomug with some of the best darters and hearty drinkers on the planet. Apool shark from Seoul. Atough-shooting “working girl” from Ho Chi Minh City. An eleven year old hustler from Puerto Vallarta. From Beijing to Moscow to Sri Lanka, from Tokyo to Johannesburg, from Bangkok to Bombay, I’ve stood at the line — often in the most unbelievable of circumstances.

There are two experiences however, that remain particularly special in my memory.

Some years ago I found myself in Bombay scouring the streets and back alleys for a game of darts. Thanks to a twelve year old boy named Johnny I finally found a game, sort of, but en route my search crossed the line between a simple adventure and a sort of awakening. The day made a difference in my life.

As I was looking for a taxi, a dirty little boy approached me with his sisters, begging for money for milk. Quickly we struck deal. In return for five cartons of powdered milk, Johnny agreed to serve as my guide for the day. After a quick walk to a grocery we hopped into a cab together.

I showed Johnny my darts as we sat in the back of the cab and explained what I was looking for. He held them in his hand. I showed him how to aim them and pretended to throw at an imaginary board. I then carefully tucked them back into their case.

We talked as we cruised the city. I learned that Johnny had no home — he lived with his family in cardboard boxes in a vacant lot. I learned that his mother was dead and his father drank and had no job. I learned that Johnny hadn’t attended school for years because he had to earn money for food. He’d learned his English from tourists like me.

We went to the zoo and circus. We made our way to the top of a cliff to gaze at the Bombay skyline. We toured the glitzy high-rise buildings at Nariman Point and ate somosas at the five-star Taj Hotel across from the famous Gateway to India monument. We watched snake charmers coax cobras out of wicker baskets on the waterfront. For hours, perhaps for the longest stretch in years, not once did the thought of throwing a dart cross my mind. The same could not be said for Johnny.

As night began to fall the little boy took charge. The taxi driver began to hit the bars, one after another. We’d stop. I’d run in. I’d locate a snooker table and have a beer. I’d dash out. But Johnny was undaunted. He insisted he knew where I could get a game in Bombay.

I found myself at the end of a dark alley. As we headed into the dark I could hear Hindi voices and the familiar rhythmic thunking of a game in progress. As we drew closer and moved into the dim light, I could not possibly have been more astounded at the sight before me. There, lying in the dust was a huge, ringed, tree stump. Dangling from it was a knife. And standing but ten feet away from me were four blokes holding more knives!

I didn’t actually throw during this trip to India. What I did was make a friend. And as I’ve written, I learned a lesson. A homeless kid with a limited future reminded me that, sometimes anyway, there’s a little bit more to life than darts.

On another occasion getting to where I threw required a harrowing three-hour flight in a beat up old Cessna — without maps or radar — through stormy African skies. To stay safely below the turbulence we cruised just above the canopy of the rainforest and in and out of the mist that rises so eerily from the trees.

To suggest that I actually know where I was when I stood at the line this night would be a serious stretch. I was in the Congo somewhere. Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.” Primitive people. Mysterious sounds.

I was somewhere east of Gabon and south of the Central African Republic. The closest collection of people was some twenty miles away in a Bantu-occupied mud-hut village called Mbomo. The barefooted tribesmen here are darters from way back. They blow the poisoned-tip version from little bamboo tubes.

The largest so-called major cities, Kinshasa, Zaire (site of the famous Ali-Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle” in 1974) and Brazzaville (Congo’s capital), are, at best, a week to the south by way of the Le’Koli and Congo Rivers. Just to the north is the pristine “Last Eden,” the Nouvabale Ndoke Forest.

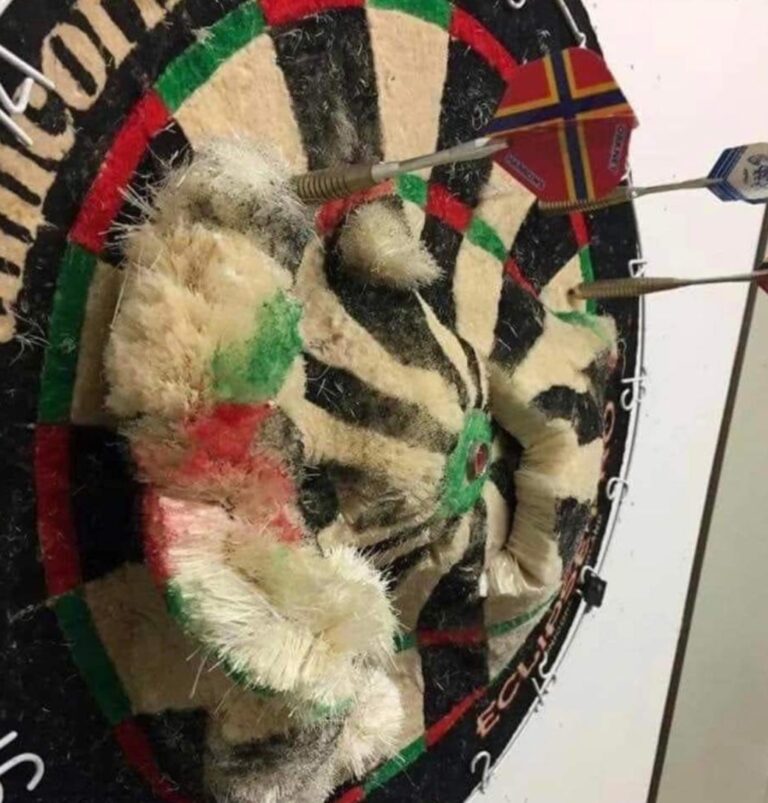

What I can guarantee about wherever I was is that the darts set up was excellent. This is because I hung the board myself. I bought it. I carried it from Johannesburg in a bag. I nailed it up with a rock I found in the bush, to a tree by a bend in a river. This board has to be hung as far away from the civilized world as anyone can get.

I’m not sure what numbers most in the African night — the stars twinkling in the incredibly vast sky or the fireflies flitting like so many scraps of glitter against the darkness of the ancient forest. Movement is constant. Sound is incessant. The lights of the night seem to dance to the symphony of a billion unseen creatures. The “thunk, thunk, thunk” of my darts only added another instrument to this uniquely African chorus.

I threw alone this night. My concentration has never been better.

My return to the real world was wilder than my journey from it. The second plane was even more decrepit than the first. As we landed on dirt airstrips at village after village, people fought with each other and the pilot to get a seat. Seriously overweight, carrying a good half-dozen more than its capacity, the plane lumbered its way back to Brazzaville. Sandwiched between a woman dying of AIDS, a shackled elephant poacher and a baby gorilla in desperate need of a diaper, I held my darts close and hoped for the best.

Anyway, if you’re ever trudging through the Congo rainforest and happen upon a lonely dart board dangling from a tree, enjoy your game. You can thank me for setting it up — if you ever get back.

Oh, there are other stories. So many of them…

There was the night in the dark and mist in the middle of nowhere, and against the better judgment of everyone I knew, that I pulled up to the gate of Diepkloof Prison — home to some 20,000 killers and rapists and worse — in Soweto, South Africa. Before me loomed a sprawling cement fortress, surrounded by consecutive two-story high walls of barbed wire. Soft light from inside illuminated the bars on the cellblock windows. I could see the movement of the forgotten souls inside. This night I threw against the prison guards… and felt bad about having a good time.

Once in Hanoi, in the former North Vietnam, in a bar called the Spotted Cow, I played against a fellow named Quyuh. Thirty years prior we could have just as easily been chasing each other with rifles through the slosh of a rice paddy. This night when I finally got the better of the guy, he simply shook my hand, smiled and said “good game” and then — in what I guess is some sort of local display of resignation — smashed an empty beer can into his forehead. It felt good to have a friend, instead of an enemy.

Once in Venezuela I found myself in the fog among the legendary billion-year-old table-rock formations (called tepuys) that shoot into the clouds from the jungle. From this very spot Sir Arthur Conan Doyle drew inspiration for his book “The Lost World.” From the highest of the tepuys, Auyan-Tepui, the cool water of Angel Falls tumbles eight times farther than the water over Niagra. Here in the undergrowth thirty-foot anacondas slither and remarkable carnivorous plants chomp the unsuspecting bug. Razor-toothed piranha lurk in the water. If one is lucky, they might see the recently discovered fruit-eating fish — which leaps in the air to grab nourishment from the trees. It is near here in the small indigenous village of San Raphael where I was coached in the art of “cerbatana” (blow darts) by a Pemone Indian named Carlos. We focused foot-long bamboo projectiles at a mark on a tree. I lost 2,000 bolivars (about four dollars) and headed on. I felt humbled.

In Kathmandu, Nepal I once threw at a bar called the Carpe Diem. I stood at the line at the foot of Mt. Everest, where the clouds touch the sky and the sky touches the heavens. I felt awe.

In Bangkok, Thailand’s notorious Patpong District — at a bar called Cosmos in the middle of the wildest stretch of nightclubs, strip joints, whore houses, con artists and who-knows-what-else that exists anywhere on earth — a 78 game shot against the owner of the bar once earned me the opportunity to select my reward from among a short-skirted bevy of bargirls. I traded my winnings for a bottle of beer. I felt silly.

Recently I threw in a new bar called City Slickers in New York City. Late at night, as I wound my through the traffic out of the city, two huge, parallel beams of light appeared outside my window. They reached from the ground and shot gallantly into the sky. They reached from Ground Zero into the heavens. I’ve never felt so sad. Or so proud.

Time and again I am reminded of how special the sport of darts really is. The ability of shooters from extraordinarily different cultures, who don’t share a lick of language between them, to compete and share in the humor and tension of a game and even debate the finer points of play, is almost uncanny. I suppose this is possible because of the “language of darts,” that special connection… that unique ability to communicate, that simply exists between people who share a love for the sport and a basic understanding of the rules.

For a couple of darters, who under normal circumstances couldn’t give each other directions to the loo, to come together and enjoy a few games of darts over a beer and under the smoke in the back room of a neighborhood pub, seems to be the most natural thing in the world.

My darting experiences may be unique. I suppose I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to travel and step to the line in such unusual circumstances.

But at the end of the day my experiences are not so different than those of any other darter, recreational or professional.

No one of my experiences is any more special than the next.

But together, they are a collection of incredible memories.

In “Dartoid’s World” throwing darts in a little bar in Beijing is no different than blowing darts in the middle of the rainforest.

Playing a stranger in Reykjavik, Iceland is no different than to playing a stranger in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Throwing against a friend in league is no different than throwing against John Lowe in a tournament.

In “Dartoid’s World” throwing darts is nothing more than a labor of love.

It is my honor to be able to share my “world” with you.

From the Field,

Dartoid