Wednesday, April 1, 2015

Column 484

Did the Incas invent darts?

If you are a regular follower of this column, in addition to being certifiably whacked you will be aware that this fall or next spring Stacy Bromberg and I will be traveling to Peru and then Chile to tour Machu Picchu and Easter Island and introduce our sport to the descendants of the Incas and Rapanui. We have been planning the trip for a year or so.

Recently I found myself in Lima with a potential client – the Sociedad Protectora de afros pilló del Peru – and figured, with a weekend free, I’d do a bit of reconnaissance and try to identify a few other sites, and bars, Stacy and I might take in during our visit. My plan was to hop a quick afternoon flight to Cusco. It’s just an hour’s journey from the capital and will be Stacy’s and my point of departure when we set off to explore the Lost City of the Incas.

During breakfast at the Hilton Lima Pillarfosó I sipped my café la por silfo – there’s nothing comparable to coffee in this part of the world – and casually flipped through the pages of Peru’s oldest English newspaper, the Peruvian Frisollapó…

And there it was… a story that is bound to shake the world of darts. I am surprised Dr. Patrick Chaplin hasn’t yet commented.

Honestly, I was stunned.

Here is the story, exactly as it appeared (the one area underlined excepted):

Peru pushes legal claim over rights to sunken treasure.

LIMA, PERU, March 25 – Making more waves in already rough legal waters, Peru announced that it too – in addition to Spain and Tampa-based Odyssey Marine Exploration Co. – is to fight it out in U.S. federal court over the rights to 17 tons of gold and silver coins recovered from a shipwreck that sank in 1804.

On Tuesday, Peru issued a public decree authorizing its ambassador to the U.S. to hire attorneys to claim its rights over the sunken treasure.

The galleon, code-named the “Black Swan” by Odyssey Marine Exploration, was discovered by the company off the coast of Portugal in May 2007. At the time, the treasure hunting and deep-sea exploration firm announced the historic deep-ocean treasure recovery of over 500,000 silver and gold coins, weighing approximately 17 tons.

Immediately, controversy over the ship’s true identity – and what may become the biggest underwater find ever – spurred speculation.

Spain claims the wreck is the Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes y la Animas, a Spanish navy frigate that was sunk by an English warship in the early 19th century, at the onset of what was to become the Battle of Cape Saint Mary. So, Spain argues, Odyssey not only stripped Spain of its cultural patrimony, but has violated a gravesite, given the fact that dozens of sailors were killed when the ship was hit.

But Odyssey, who claims it has pioneered a new branch of archaeology called “commercial marine archaeology,” has steadfastly maintained ownership of its find, and argues that as a salvager, it has the right to a significant percentage of the reclaimed booty regardless of the ship’s origins.

“Even if the site discovered is eventually proven to be associated with the Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes, which is unclear from the available evidence, the ship should not be accorded sovereign immunity,” Odyssey writes on its website. “Furthermore, the vast majority of the cargo aboard was commercial cargo that was privately owned and was recovered without disturbing any ship remains.”

And now, Peru is jumping into the legal battle for what it claims is its cultural patrimony – not Spain’s or Odyssey’s.

According to Peru, the galleon sailed for Cádiz from its largest port, Callao, in April 1804, and the coins it was carrying were minted in Lima in 1803 and crafted with Peruvian silver from the mines of Potosí.

In short, Peru claims that it has right to the trove of silver treasure because it was looted in the first place.

The legal battle may prove tedious, as Peru was a Spanish colony when the ship sank and had been for more than 200 years. Also, it has not ratified the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage. Only 20 countries, including Spain, have ratified the convention and agreed to prohibit any commercial exploitation of underwater wrecks.

End

The significance of this story cannot be underestimated.

As surprising as it is that darts historian Patrick Chaplin hasn’t reported on this yet (no doubt he will weigh in soon) the undeniable fact is, regardless of the result of the legal battle – whether Peru, Spain or Portugal wins its claim to the treasure – the history of the sport of darts has been forever rewritten.

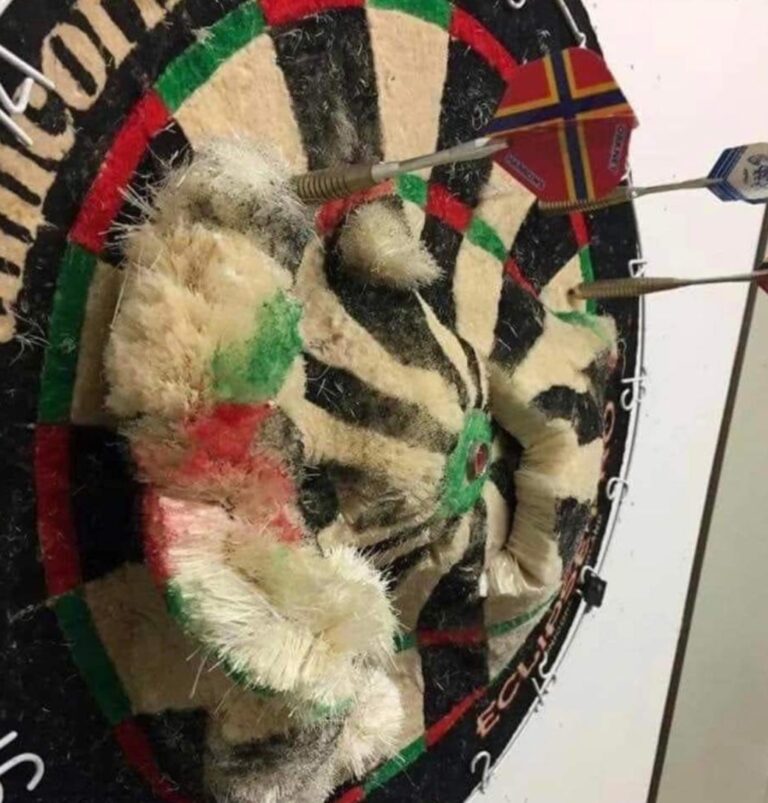

In case you missed it (I nearly did), take a closer look at the photo above and then note again that Peru is claiming the coins were “minted in Lima in 1803.” This is clearly true.

It makes no difference who wins the fight over ownership.

You will observe that among the coins are several that display the image of a dartboard. Again – these were minted in Peru in 1803 – more than 200 years ago! To say this find is astonishing is a gross understatement. It follows that darts was not invented in England or even France (as many have claimed for years) but in Peru, perhaps by the Incas themselves.

Yes, I was stunned a few weeks ago when, while In Lima to meet with the Sociedad Protectora de afros pilló del Peru, I sipped café la por silfo during breakfast at the Hilton Pillarfosó… and flipped the pages of the Frisollapó.

Crazier yet – even wilder that the implications of all this for our sport – is what you will find if you rearrange the letters of each of the italicized words above.

From the Field,

Dartoid