February 1, 2004

Column 154

Pae-por

A famous author once observed…

“The heartland of Southeast Asia has always been on the edges of civilization. The great empires, such as the Pagan in Burma, Sukhothai in Thailand and Angkor in Cambodia, were built in the plains, where rice grows easily and there are trade routes to the sea. For the rulers of the time — as well as for the governments of today — the writ of law petered out in the jumble of limestone hills and teak forests of the north. From the Tibetan Plateau, of the Himalayas, several great ranges of mountains flow out in a big curve, first east, then sweeping southward. Lying between them are the upper reaches of three great Asian rivers — the Yangtze, Mekong and Salween. Where these rivers diverge, the hill country spills out in a disorganized mass, around the borders of Burma (now Myanmar), China, Laos and Thailand.”

This is the exotic Golden Triangle, where the poppies grow and my little friend lives…

“The roads are pathetically inadequate and trails winding from ridge to ridge are the normal means of contact and transport. Dusty in the dry season, slippery with mud when wet, they link hamlet to hamlet across hundreds of miles of broken terrain. Little wonder that these hills have long had a reputation for lawlessness and intrigue, from the fiercely independent princes of Burma’s Shan States to roving mercenary armies. Their remoteness has also made them the stronghold of mainland Asia’s last ethnic minorities – the hill tribes.”

Her name is Pae-por. She is eleven years old…

Pae-por’s a member of the Karen hill tribe (known to the Thais as Karieng and Yang). No one knows for sure from where her people arrived. It’s possible that they came originally from Southwest China or Tibet, but there’s no hard evidence. Probably they arrived from the west, along the lower Salween River in Burma.

Pae-por was orphaned when she was only three. Her mother died of malaria and her father was killed in a bizarre accident while working in the fields. He was trampled by an elephant.

Since her parent’s death, Pae-por has been in the care of her aunt and uncle. They are also poor crop farmers who earn barely enough to feed their own four children. Their living conditions are very poor. They have no plumbing and must use the nearby forest as a toilet and dumping ground for garbage. They survive on less than a dollar a day.

The moment I learned about Pae-por’s situation I knew I had to help her. I wanted to meet her. I knew that although she was attending school, little girls where she is from are at high-risk for dropping out. I knew that if she quit school chances were that she’d eventually migrate to the city in search of work to help support her family. Young girls like Pae-por are often overlooked for regular jobs. Instead, they are lured into the dangerous world of child prostitution.

So I raised some money.

I wrote to a list of people who I knew cared…

“Pae-por’s dreams are no different than any other little child’s dream. In almost every way, just like children who play together in the yards in your own neighborhood, Pae-por has the same simple aspirations. She wants to play and have fun. She wants to go to school and do well and someday have a family of her own. The difference between Pae-por and the children we know here at home is very basic — but huge. Pae-por was born into circumstances that she had no control over. She was born poor. And then her parents died. All in a country notorious for child prostitution, child malnutrition and child injustice.”

With a check in hand I traveled to Bangkok where arrangements had been made for Pae-por and I to meet. She was shy at first but warmed up. With the help of a translator we talked for almost two hours.

I asked her what was different about Bangkok compared to where she lived. With out hesitation, she replied: “the crowds, traffic and tall buildings.” She told me about her dog, friends, a baby elephant that lived in her village and the waterfall where she played. She invited me to visit her home. I told her I would.

Before I returned to my home in Pennsylvania I arranged for her uncle to receive $1,000 so he could start a small chili pepper farm. I also arranged for Pae-por to receive the funds she needed for books, pencils and a school uniform.

Four months then passed. We exchanged a few letters and photographs. She sent me pictures of everything she was going to show me when I came back. I sent her a large picture book about America with lots of colorful photographs of famous sites like the Grand Canyon and the Statue of Liberty. I sent her snapshots of my wife and dog. I told her I would be bringing a special gift.

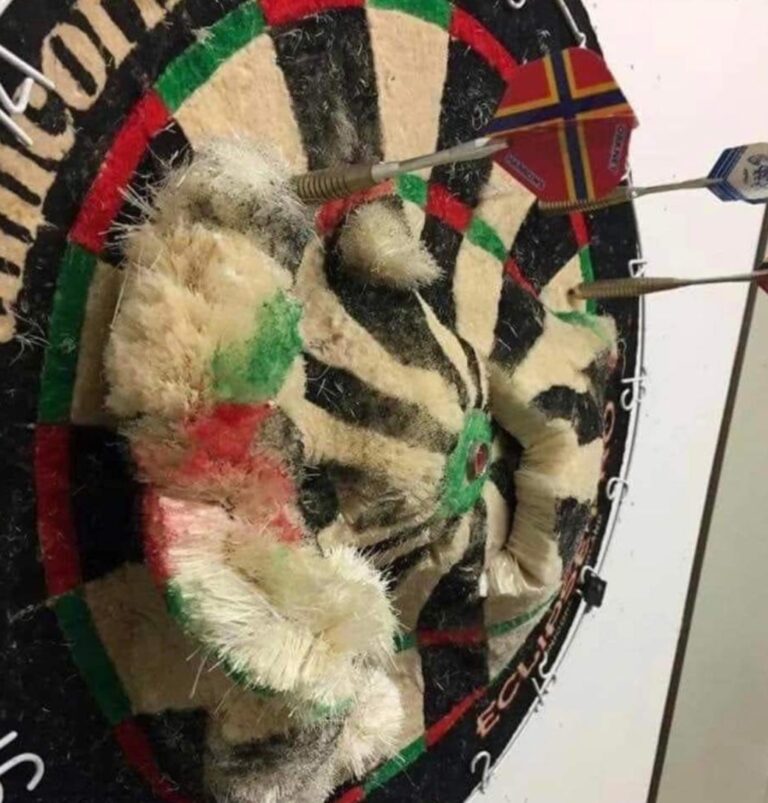

It was in the heart of the rainy season that I ventured my way to the middle of nowhere, in northern Thailand, just a few clicks west of the Myanmar boarder, near the frontier town of Mae Sot. The dartboard and darts where packed safely in my bag.

I was swarmed when I finally arrived. Nearly the entire village of some two-hundred people came to great me.

The women gave me gifts — brightly colored traditional weavings and beaded jewelry. The village leader, Peo-por’s uncle and several of the other men invited me up to the crude veranda on one of the stilted log houses to squat with them in a circle and pass around an old Jack Daniel’s bottle filled with home-brewed rice wine.

Later Pae-por and her friends led me on a several kilometer hike through the hills to see her waterfall. Along the way we passed a mahout. Mahouts are among the poorest of the poor in Thailand. Not long ago, when commercial logging was legal, they survived — though just barely — by providing the elephant labor to haul the large trees. Today both the mahouts and their elephants are unemployed. They are starving. But where Peo-por’s lives this man, who has nothing but an old elephant, is the wealthiest person in the clan. We had our pictures taken with the elephant.

We slogged on and eventually arrived at a small river. Balanced across it was a long bamboo pole. Pae-por scampered across it in a moment. I was unable to balance — possibly because of the weight and awkward way the dartboard was stuffed into the pack on my back, more probably because I’m not eleven years old.

Still soaked, hours later I found myself back up the hill and again on the veranda in the trees. Around and around the circle the rice wine traveled. I was served some kind of soup in a dirty bowl. For while we leafed through the book I had sent from home. I explained to Pae-por and her friends what America was like.

Too soon the time came for me to leave. It was time to give Pae-por the gift I had brought — to nail the board to a tree and show her and her friends how to play. She and her entire village had taken me into their lives and shared the pleasures that were important to them.

But I couldn’t reciprocate.

My gift seemed trivial and unimportant — insulting in the face of all they had done for me.

Instead, I discretely handed a worn envelope to the village leader. “Help everybody,” I whispered.

I waved goodbye and began the long trek back to civilization, a better person for the experience I’d had — but just a bit uncertain how I was going to make it home with little but a dartboard to my name.

From the Field,

Dartoid